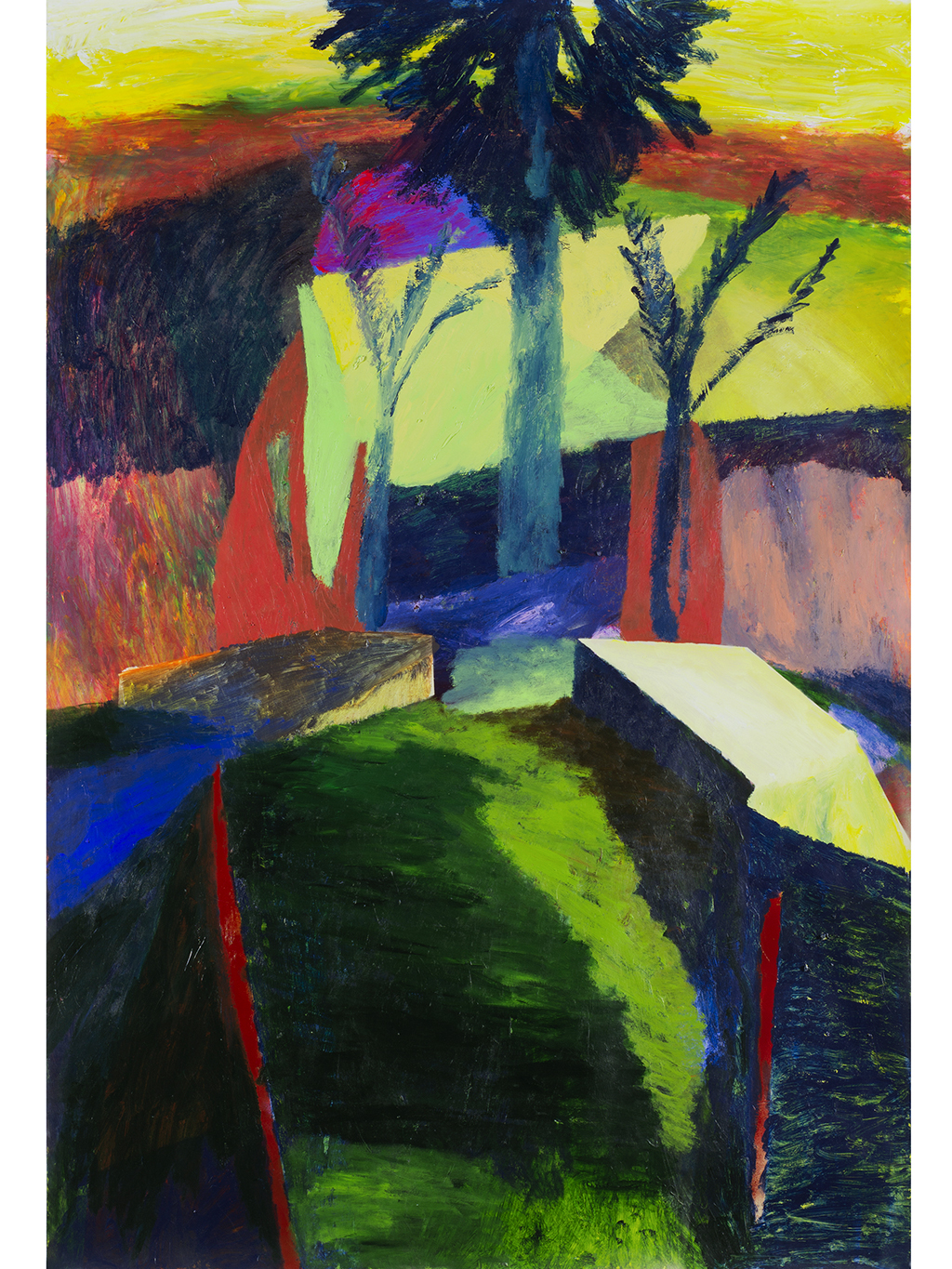

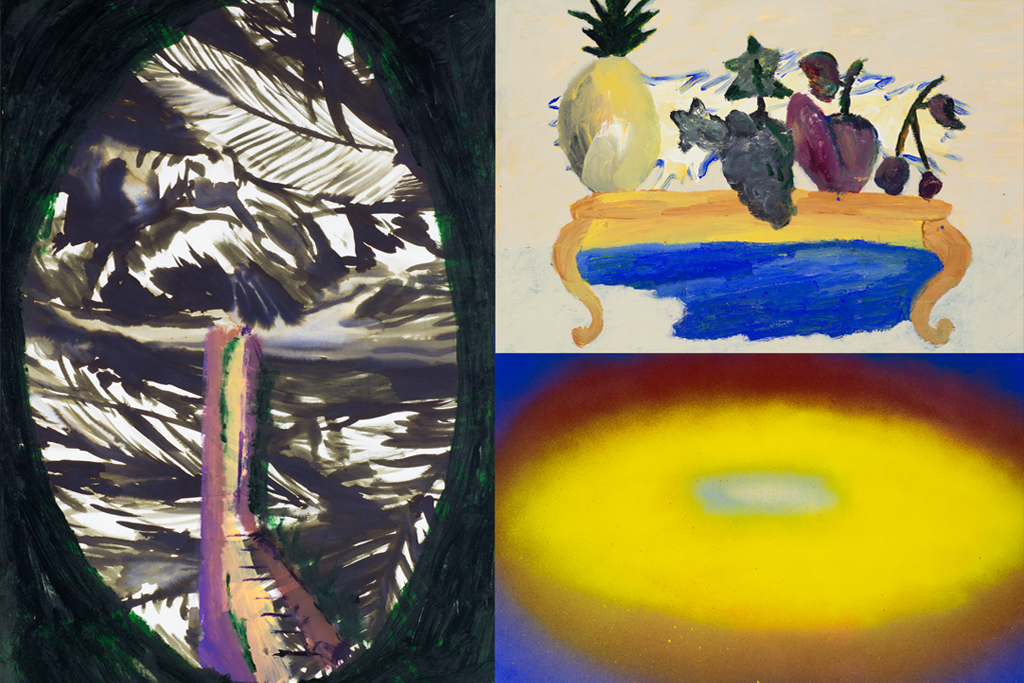

NADIE LO SABE TODO, Exposición con Leandro Feal, Azkuna Zentroa. Bilbao 2017

NADIE LO SABE TODO, Exposición con Leandro Feal, Azkuna Zentroa. Bilbao 2017

La conquista de lo contemporáneo

Hay un momento del Arte Contemporáneo que tiene su apogeo en los años ochenta el siglo XX, coincidiendo con la crisis del comunismo o la promulgación de la Era Global: esta época en la que -gracias al eterno presente del fin de la historia y el esplendor de Internet- todos viviríamos simultáneamente.

Esas fechas fijan una extraña manera de narrar el arte. Justo cuando, en los catálogos, los currículums empiezan a escribirse hacia atrás. Esto es: desde el presente hasta los primeros pasos de los artistas. En esa circunstancia, el relato del arte sobre sí mismo evidencia un trastorno temporal y, asimismo, un preocupante horror al futuro. En ese punto, el currículum del artista queda convertido en un artefacto freudiano, un pertrecho a través del cual emprender un viaje al útero materno hasta llegar al nacimiento, natural o artístico, del protagonista.

Esa historia “al revés” guarda más relación con la ficción que con la crítica o la teoría. Es un periplo novelesco que está más próximo a El curioso caso de Benjamin Button, de F. Scott Fitzgerald, o Viaje a la semilla, de Alejo Carpentier, que a cualquier pieza de Arthur Danto o Brian Holmes. Esos dos cuentos ilustran el grado cero de un presente que le da la espalda al porvenir. Y explican por qué cualquier currículum despachado en un catálogo resulta poco fiable. En buena medida, porque ya sabemos el destino que nos plantea. Pero, sobre todo, porque se diferencia notablemente de la biografía. Si el currículum privilegia las honras, la biografía escarba en un material más escabroso. Si el currículum vela, la biografía desvela. Frente a la asepsia profesional del currículum, se levantan las vanidades y resbalones que arman esa novela del arte que no ha parado de crecer en los últimos años. Mientras el currículum retrocede hacia una zona protegida, la biografía avanza hacia ese lugar del futuro donde nos espera la intemperie.

Así pues, hablar hoy de Arte Contemporáneo implica no decir nada. (O casi nada, que no es lo mismo, pero es igual). La contemporaneidad del arte ha dejado de reflejar una magnitud temporal o tangible para invocar una dimensión “profesional” e inasible. Ha quedado como un comodín que –a base de combinar a Fukuyama con Danto- ha terminado por reforzar uno de los más rentables géneros estéticos: ese que supone el fin del arte como una de las bellas artes. Un género en gerundio continuo, dicho sea de paso, que va despidiéndose sin asumir de manera radical su lapidación definitiva.

Contra esa despedida infinita, es pertinente que los artistas recuperen la historia, que indaguen en los pormenores de la memoria colectiva o se remonten al origen de lo que somos y, aún más, de lo que hubiéramos podido ser. Contra esa despedida infinita, es también pertinente que intenten atrapar el tiempo, aunque sólo sea el de la hora exacta que marca cualquier reloj en otro lugar.

Esta tarea podría servirnos para certificar lo que ya nos anunció Paul Virilio: la globalización no implica el fin de la historia sino el fin de la geografía. De modo que el reto no está en aceptar la simultaneidad que propone la cultura digital, sino en buscarnos como contemporáneos, sujetos con un tiempo común por más que pertenezcamos a mundos distintos.

No se trata, pues, de aplaudir la falsa inmortalidad de un arte dedicado a contarse hacia atrás. Se trata de poner en marcha el reloj hacia delante, a partir de nuestro calendario mortal. Lidiar con el tiempo para descolocar las jerarquías de las historias oficiales, las fronteras oficiales, las cronologías oficiales. Para indagar en lo que no sabemos de la historia colectiva o en lo que ignoramos de la hora privada. En el supuesto valor absoluto de la primera y en el supuesto valor relativo de la segunda.

De muchas maneras, Taxio Ardanaz y Leandro Feal se cruzan en este empeño. El primero, remontándose a las causas de la revolución cubana. El segundo, emergiendo de sus consecuencias. Ambos, intentando escudriñar la contemporaneidad de aquel acontecimiento hoy casi remoto.

Porque las revoluciones son también un acto generacional y egoísta. De ahí que el mismo Fidel Castro lo dejara claro desde el principio: “Nosotros no estamos haciendo una Revolución para las generaciones venideras, si esta Revolución tiene éxito es porque está hecha para sus contemporáneos.”

Es por eso que las revoluciones siempre se han manifestado con cañonazos contra los relojes. Asaltar la Bastilla o el Palacio de Invierno ha implicado conquistar el tiempo. Por eso, si bien todas las generaciones no hacen la revolución, todas tienen el deber de poner sus relojes en hora. O, al menos, de conquistar la contemporaneidad artística donde la contemporaneidad política ya había sido conquistada.

Iván de la Nuez

Conquest of the contemporary

Contemporary Art saw its heyday in the 1980s coinciding with the crisis of communism or the announcement of the Global Era. A period in which we would all live simultaneously thanks to the eternal presence of the end of history and the golden era of the Internet.

These moments in time set a strange way of narrating art, just when CVs in catalogues start to be written backwards, i.e. from the present to the artists’ first steps. In this circumstance, the story of art about art itself experiences a temporary disorder and, at the same time, an alarming fear of the future. At this point in time, the artist’s CV becomes a Freudian artefact, an instrument to set off on a journey to the mother’s womb back to the protagonist’s natural or artistic birth.

This “backward” history is closer to fiction than to critique or theory. It is a novelesque journey which is closer to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, or Alejo Carpentier’s Journey to the Seed, than to any work by Arthur Danto or Brian Holmes. These two stories illustrate the zero degree of a present which turns its back on the future. They also explain why a CV included in a catalogue is not very reliable. It is largely because we already know what destiny has planned for us, though chiefly because it varies considerably from the biography. Whilst a CV pays tribute to achievements, a biography delves into the muck and dirt. If the CV safeguards, then the biography reveals. Against the CV’s professional asepsis, the vanities and slip-ups that put together this art novel which hasn’t stopped growing in recent years arise. While the CV retreats to a safeguarded area, the biography advances towards that place in the future where the inclemencies await us.

In other words, talking about Contemporary Art means to say nothing (or almost nothing, which is not the same, but it does not matter). The contemporariness of art no longer reflects a time or tangible magnitude to invoke a “professional” ungraspable dimension, but rather a wildcard which by combining Fukuyama and Danto, has ended up reinforcing one of the most profitable aesthetic genres, i.e. that which means the end of art as one of the fine arts. A genre in continuous gerund which, by the way, keeps saying farewell without radically assuming its final lapidation.

Against this infinite farewell, it is important for artists to recover history, to delve into the details of collective memory or to go back to the origin of who we are and, even more so, to what we could have been. Against this infinite farewell, it is also important they try and trap time, even if it is only the exact time any clock strikes in another place.

This task might serve us to certify what Paul Virilio announced, i.e. globalisation doesn’t mean the end of history but rather the end of geography. Therefore, the challenge does not lie in accepting the simultaneity proposed by digital culture, but rather in looking for ourselves as peers and as subjects with a common time even if we belong to different worlds.

So, it is not a question of applauding a false immortality of an art devoted to being told backwards. It is all about setting a clock forward from our mortal calendar. In other words, we have to struggle with time to disconcert the hierarchies of official histories, official frontiers, and official chronologies. We need to delve into what we do not know about collective history or what we ignore about private time, into the supposed absolute value of the former and the supposed relative value of the latter.

In this struggle, Taxio Ardanaz and Leandro Feal cross with each other in many ways. Taxio Ardanaz goes back to the reasons behind the Cuban revolution while Leandro Feal emerges from its consequences. Both endeavour to scrutinise the contemporariness of that virtually remote event today. Revolutions are also a generational and selfish event, and even Fidel Castro stated it loud and clear from the beginning: “This is not Revolution for future generations. If this Revolution is successful it is because it was brought about by your peers.”

This is why revolutions have always manifested themselves volleying against clocks. Storming the Bastille or the Palace of Winter has involved conquering time. Therefore, although not every generation leads a revolt, they all have to set their clocks to the right time, or at least, they all have to conquer the artistic contemporariness where political contemporariness has already been conquered.

Iván de la Nuez